Fun Book Recommendations To Help You Prepare for the Apocalypse

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

As if we don’t have enough drama in our life just now, here are a few novels that suggest humanity may never recover from the pandemic.

In her book Oryx and Crake, Booker Prize-winner Margaret Atwood tells a cautionary tale about a near-future time when the world has become a wasteland due to genetic experiments gone horribly awry. On her blog, Atwood describes the subtext to her depiction of bizarre crossbreeds and eerie landscapes: “What if we continue down the road we’re already on? How slippery is the slope? What are our saving graces? Who’s got the will to stop us?”

“Several of my close relatives are scientists,” Atwood writes, “and the main topic at the annual family Christmas dinners is likely to be intestinal parasites or sex hormones in mice, or—when that makes the non-scientists too queasy—the nature of the universe.” She describes that she has been clipping small items from the back pages of newspapers for years and notes with alarm that trends derided ten years ago as paranoid fantasies have become possibilities, then actualities. She wrote this a nearly twenty years before Covid-19.

It was, in fact, during her writing that 9/11 occurred.

“It’s deeply unsettling when you’re writing about a fictional catastrophe and then a real one happens,” she says. “I thought maybe I should turn to gardening books—something more cheerful. But then I started writing again. Because what use would gardening books be in a world without gardens, and without books?”

Cormac McCarthy has no such concern for runaway technology in his 2006 bestseller The Road (adapted as a film that received mediocre reviews). Its stripped-down storyline describes a man and his young son trekking through an unexplained nuclear-winter landscape in search of food and warmth as they run from bands of cannibalistic outlaws. Scavenging in abandoned towns and withered forests, they provide each other with just enough encouragement to not lie down and die. It is a spare book, filled with hypnotic prose and poignant depictions of emotional longing. Indeed, for all its stark, ash-gray finality, it is McCarthy’s belief in love’s power to redeem when there is no hope for redemption that makes The Road such an engrossing portrait of things to come.

Had the current pandemic not happened, such novels about humanity’s demise might have continued to reside on Amazon’s science fiction page. Now, however, fiction looks more like fact every day, and daily reports about the Corona virus’s spread share space with deeply troubling reports of melting ice caps and global warming. In an often-quoted New York Times Op Ed, Robert Wright, Senior Fellow at the New America Foundation, describes three ways the world might come to an end.

- Classic nuclear Armageddon. This plays out on the level of world governments and has been in remission since the end of the Cold War. However, current political circumstances—particularly given the Trump administration’s penchant for waving red flags at North Korea and other hostile governments—could revive it.

- Terrorism. This occurs on the ground, below governmental radar screens. As the ranks of terrorists grow, and if the world further polarizes into “them and “us,” the odds increase that a rogue terrorist organization could acquire the technology needed to hold the world hostage.

- Eco-apocalypse. Whether it is a viral pandemic, rising sea levels, or other environmental threat, solving climate change requires global cooperation. Many governments in general, and the U.S. in particular, have been going in the opposite direction. America’s withdrawal from nearly all climate-related commissions and its reversal of all but a handful of Obama-era safeguards have raised this option to the top of the pile of end-of-days scenarios.

Wright’s solution to this dire prediction is that “we may have to cultivate our moral imagination, putting ourselves in the shoes of people who hate us. This understanding,” he writes, “involves seeing how, from a certain point of view, hating America ‘makes sense’—and our evolved brains tend to resist that particular epiphany.”

Wright has reason for concern. For most other nations currently, there isn’t much impetus to like America just now, and plans to save the world are being developed without U.S. participation. The reason is simple: the rest of the world can’t count on U.S. to either participate or keep its word about anything. If cooperating suits the current administration’s political or economic agenda, the U.S. cooperates. If not, it doesn’t. To quote poet George Meredith, “In tragic life, God wot, no villain need be! Passions spin the plot: We are betrayed by what is false within.”

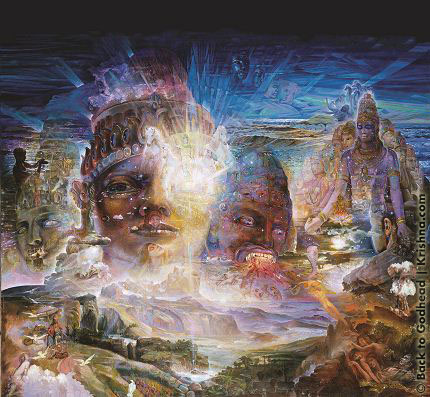

Like their notable predecessors Brave New World and 1984, the more recent Oryx and Crake and The Road admit the existence of something “false within” that compels post-modern man to stop at nothing to get what he wants. In remote history, the Bhagavad Gita used the following words to describe those who would put the world at risk for their own ambitions:

“In this world there are two kinds of beings, one divine and the other demoniac…. The demoniac do not know what is to be done or not done…. They say this world has no God in control, that its main moving force is sex, and following such conclusions they engage in unbeneficial, horrible work that can destroy the world… ‘So much is mine now,’ they tell themselves, ‘and it will increase in times to come. I have killed my enemy and soon others shall also die…’ ”

Unlike novels, which offer no way out of the abyss, the wisdom text Bhagavad Gita reveals a frame of consciousness that has no borders. There is not the slightest hint of nationalism in the bhakti culture: it is not the property of India, of Hinduism, or any political party. Devotion—the vision of all life as sacred—compels practitioners to nurture compassion, respect nature, and work for the wellbeing of all. Pandemics and end-of-days devastations may be unavoidable, but in cultures guided by love of all life they are not irreversible.

Some scholars point to Chapter 11 of the Gita as a kind of Apocalypse, for it is here that Krishna displays his ability to devour the universe in an explosion of nightmarish imagery and atomic fire. Still, nowhere does Krishna say that this is how things must be. The Gita is overall an optimistic work that resides at the bright end of the literary spectrum.

Guided by the Gita’s teachings, members of the bhakti community benefit from resources that writers and peacekeepers might want to consider when envisioning potential futures for humanity: (1) knowledge of the fundamental oneness of life on its substratum of consciousness, and (2) faith in a beneficent divinity capable of resuscitating even the most devastated of post-Apocalypse scenarios. The two tools—knowledge and faith—go together. Knowledge without faith remains abstract and does not assure change in behavior; and faith without knowledge remains blocked on the level of sentiment and may even fuel fanaticism.

Unlike the wildly popular Left Behind series, which also depicts an end-of-time scenario, the Gita does not posit any exclusive clubs for those who will be saved. A simple acknowledgment that the sanctity of things precedes selfish interests suffices for a multitude of unseen resources to kick in. Amazing, really, what even a hint of humility can do to set humanity back on track.

The Gita may lack some of the page-turner qualities of the current spate of Apocalypse literature (for that you’ll need to revert to the larger work Mahabharata of which Gita is but a handful of chapters). Still, for an ending that leaves readers feeling hopeful and a bit more cheerful, Gita deserves the Pulitzer.

Books mentioned in this article:

- Oryx & Crake by Margaret Atwood

- The Road by Cormac McCarthy

- Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

- 1984 by George Orwell

- Left Behind series by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins

- Bhagavata Gita As It Is commentary by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami

- Mahabharata retelling by William Buck

The article contains affiliate links. Gita Wisdom may receive a small commission from the purchases through these links.