Estimated reading time: 16 minutes

A young man pursues the meaning of creative expression

I came of age in the mid-Sixties and attended expensive schools on scholarships. That put me in a socially awkward position and I ended up spending a number of weekends on my own wandering through New York City’s cavernous museums. New York’s museums offered an unparalleled perspective on the history of art. In one afternoon, a visitor could journey on foot from prehistoric cave paintings to Renaissance pietas, and from there to pop art, op art, and the latest in Sixties psychedelia.

My favorite museums were the Metropolitan, the Guggenheim, the Museum of Modern Art, and also the Museum of Natural History where I was struck by the apparent parallel between the evolution of art and the evolution of man. First came the cavemen, with their cave paintings rough, simplistic products of an obviously lower order of intelligence. Then, as man began wearing clothes, shaping tools, and tilling the earth, he produced the crude religious paintings and iconography of early civilization. Finally, as man grew more civilized, art grew more sophisticated, until homo sapien was producing an artistic legacy as complex and unfathomable as his own neurological organs.

The apparent parallel evolution of art and man was too pat; it left an empty feeling in my stomach. Though my education taught me to accept such a parallel, some part of me disagreed with the premise that art viewed chronologically was synonymous with art viewed progressively. The free-floating Calder mobiles appealed to my sense of aesthetics, but did that place them somehow above the simpler works relegated to sections marked “Tribal Talismans”? The sensual curves of a Moore sculpture attracted my adolescent mind, but were they “better” than the three-thousand-year-old works designated “Hindu Deities”? The open-ended canvases of Jasper Johns made me think about how his work affected me, but did I feel any less affected by the delicate miniature encrusted with gold and labeled “Krishna: Indian Forest God”?

By Chandravathanaa – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

These exhibits were consistently arranged to suggest that objects of art were no more than cultural artifacts. The arrangement was no doubt the work of anthropologists, art historians, sociologists, and others who had a vested interest in making culture central and human history a chronological journey forward. Religious art with its references to gods and goddesses might be esthetically pleasing, but it was the vestige of a less evolved time in humanity’s past. It was art as an expression of life’s grounding in physicalist reality that had something useful to offer.

By the time I met devotees of Krishna in Paris in 1969, I’d been indoctrinated into this idea that art could change the world provided it did not depend on a theistic structure to creation. I’d attended courses with titles such as “Existentialism and Modern Art,” “Physics for Poets,” “Social Trends in Art History,” and “Picasso and the Collective Unconscious.” What these courses all had in common was an insistence on the interrelationship of the arts and the notion that art should judiciously avoid otherworldliness. Like the perfectly ordered historical art exhibits I had known during my high-school days, my university also treated art as one of the Humanities, as a subject that dealt exclusively with human meanings. Art, these courses insisted, can be understood only within the context of culture.

Krishna devotees lived with art that went beyond this notion. In those early days of the Krishna consciousness movement in France, readings from the Bhagavad-gita and group chanting of Hare Krishna took place on Sundays in the Latin Quarter, at a gray two-story hangout for students, artists, poets, and musicians. Perched precariously on a folding chair in the corner of a room that sat about thirty was a three-foot-high color poster of Gopala (Krishna), the Supreme Lord and the speaker of the Gita. The name Gopala means “cowherd boy,” and in the picture Gopala was sitting gracefully, with His arm around a calf, looking off into the distance.

“Who’s that in the picture?” I asked a devotee named Umpati who stood peeling apples by the door.

“That’s Krishna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead.”

“And the cows and trees—is that supposed to be heaven?”

“No, not heaven. That’s still within the material world. The spiritual world is different.”

I watched the devotee meticulously arrange the apple sections on a brass tray, then he placed the tray on before the poster on the folding chair and murmured prayers. A few moments later, he sat on a cushion before the group that had assembled for the class and began reading in French from the Bhagavad-gita.

“Krishna’s body,” he explained, “is not limited by material elements, as is our body. His body is not subject to laws of decay and death. And since He is absolute, He remains spiritual in all His manifestations. His appearance in wood or stone or paint transforms the material medium into His own spiritual substance. We should not think that a Deity or painting of Krishna is an idol. It is Krishna Himself, graciously appearing in a form visible to us, to help us remember Him.”

Unexpectedly, I was hearing a challenge to my long-held belief in the cultural relativity of art. Extrapolating freely, the Bhagavad-gita had this to say about art. Art can contain more than human elements. Under certain conditions a work of art can serve as a vehicle for higher, transcendental forces, whose impact on the viewer or hearer (in the case of music, drama, or poetry) will not depend on social or intellectual history. The mere act of seeing such art can produce a spiritually uplifting effect. Though intellectual awareness of the history of the image may enhance appreciation, such awareness is not prerequisite to its spiritual impact. According to the bhakti or Krishna tradition, an artistic representation of divinity is not different from divinity and can act on observers regardless of the art’s cultural significance.

I began spending evenings with devotees in their small apartment, which they had decorated with posters and drawings of Krishna in His various incarnations and of sages from the scriptural histories. None of these works struck me as artistically astute. The features were often naive, the compositions unimaginative, the proportions out of whack.

The greatest travesty, in my eyes, was that they failed to challenge the observer’s imagination. Little in any of these pictures left anything to the onlooker’s interpretive skills. They were purely representational; the spectator did not participate. There was Krishna tending His cows in His village, called Vrindavan, and there were the trees and flowers, all neatly arranged, best blossoms forward. It was clear that the artists had done their job quite well by painting what was described in scripture—but now the painting was there, and now the observer had only to gaze.

The devotees described their experience differently. Seeing Krishna in art, they explained, was for them like looking through windows onto the spiritual world. Each morning they would sit for an hour or more, concentrating on the paintings as they chanted Hare Krishna on wooden beads. Cultural significance had nothing to do with these contemplative moments. The devotees sat entranced before these paintings, which permitted them to commune with Krishna, and for the devotees that was all that mattered.

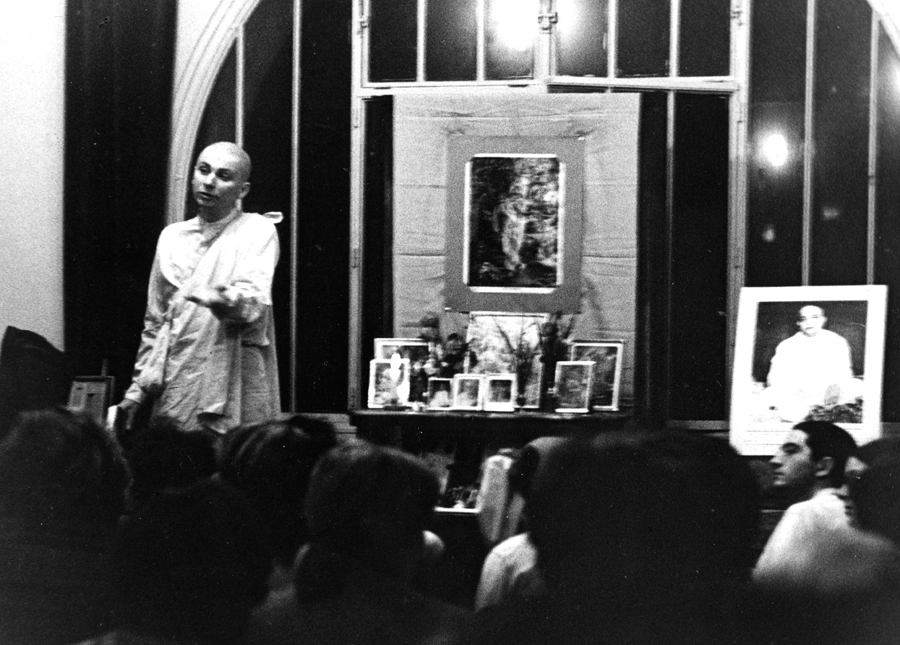

Many months later Srila Prabhupada, the founder and spiritual guide of the Krishna consciousness movement, visited Paris. By that time I had myself become a devotee of Krishna, and Srila Prabhupada’s visit seemed a good opportunity to clear up some of my lingering questions about the role of art in spiritual life. I waited until I could meet with him in his quarters, and then I dove right in.

“What is the function of art for devotees, Srila Prabhupada?”

He looked up and studied my face for what seemed a long time, then said, “It is to put things in their proper place for best utility.”

I didn’t understand what he meant, but rather than ask the same question again, I said, “Some artists might disagree. Sometimes it is considered art to take an object out of its proper place and give it a life of its own. Some artists argue that a work of art is a reality in itself and that art doesn’t depend for its value on anything or anyone else. They say that art is most beautiful when accepted as a self-sufficient reality.”

“Beauty and art are different,” he corrected. “Beauty is something that satisfies my eyes. Your eyes may be satisfied by something, my eyes by something else. According to your idea of beauty, my beauty may be unacceptable. Beauty is a kind of sense gratification.”

“Some paintings are not trying to be beautiful,” I said. “They’re trying to make a statement about the world and our place in it.”

“That’s alright,” he said, “but you asked about beautiful. There is no such thing as a standard of beauty. Just like nowadays artists make ‘beautiful’ paintings,” and he waved an imaginary paintbrush wildly in the air above his head and laughed.

“I don’t like it, but someone else may say it is very beautiful. So beauty and art are different. And for devotees art means arranging things for the highest utility. Beauty may satisfy but not have any higher utility. A picture, a poem anything is art when it serves the very best utility.”

Utility was obviously the crux of his definition of devotional art. “If someone’s work fulfills that qualification of highest utility, is he an artist?”

“Yes. An artist is one who knows the standard of best utility.”

I opened Webster’s. “One definition for artist in the dictionary is ‘one specifically skilled in the practice of a manual art or occupation, as cooking.’ So applying this to your interpretation, a cook preparing food for Krishna is an artist.”

“Oh, yes, anyone who performs his work for the satisfaction of Krishna, who knows His relationship with Krishna, is a true artist.”

That helped clarify his use of the word utility. He was defining art as any work that brings the performer out of the cycle of birth and death and closer to God. He was defining art as yoga. By this Prabhupada was not denying the need for rules of composition or balance in color and design. Rather, he was expanding the meaning of art beyond the traditional forms of painting, sculpture, music, drama, poetry, to include every field of human endeavor–a notion described in Bhagavad-gita (2.50):

Persons engaged in devotional service free themselves of both good and bad actions even in this life. Therefore, strive for yoga, which is the art of all work.

In the simple acts of devotion I’d witnessed in my first encounter with devotees—the offering of sliced apple on a tray before a poster of Krishna—there was artistry at work I could not appreciate at the time. Inspiration is communicated by the art of work as effectively as by a work of art. In simplest terms, Krishna in the Gita exhorts everyone to become an artist by performing their work as an offering of love to Him.

“In other words,” I asked, “would we say that anyone who works on behalf of Krishna, according to Krishna’s direction, is an artist?”

“Yes. A devotee knows the standard of utility. He knows how to put things in their proper place to inspire love for Krishna in himself and others.”

Srila Prabhupada stopped speaking, and a thoughtful silence filled the room. I thought back to my first days after Paris, as a devotee in the London Krishna temple, where I met a young Scottish devotee named Digvijaya. He was the temple’s cook. No one knew how to “put things in their proper place” better than Digvijaya. A simple country boy with a knack for detail, Digvijaya could turn a tray of raw vegetables into a royal feast and kept an immaculate kitchen that boasted rows of pots sparkling from the hours of patient scrubbing he had put into them. Attracted by his fastidious habits and culinary feats, I would sometimes go down to the basement work area and help him prepare an offering for the Deities.

“You like to work for Krishna in the kitchen, don’t you?” I asked him one evening.

Digvijaya looked a little flustered and went on with his cooking. Finally, he looked up and said, “Actually, I don’t consider myself advanced enough spiritually to serve Krishna directly. I’m happy just cooking for His devotees.”

This was a young man whose culinary skills could have earned him a place in fine restaurants, yet he was humble, and during our talk he revealed to me the secret of spiritual cooking.

“Don’t speculate,” he said. “The best recipes for Krishna prasadam, vegetarian dishes for Krishna’s pleasure, have been around for a long time. A good devotee chef cooks them just as Krishna has always liked them, since time immemorial.”

Now, two years later, Srila Prabhupada was confirming the same principle as the essence of spiritual art. Don’t speculate. Your work is meant to be an offering of love for Krishna, not a product of artistic ego. Let Krishna guide your efforts.

“Real art, then,” I said, “means simply to do something for Krishna’s pleasure?”

“Yes,” Srila Prabhupada replied. “That is also the definition of love: to do something for the pleasure of the beloved.”

“But what about artists as a class of people? What about art as a specific field of creative endeavor, art in the classical sense painting, sculpture, music? Do spontaneity and personal inspiration play no part in Vaisnava [devotional] art? Is the artist irrelevant if everything he does is already laid out in the scriptures?”

“All these questions will be answered when you visit the artists who paint for my books.”

Many months later I had that opportunity. At the devotee artist studios (then in Los Angeles), much was like what I had seen in dozens of other studios: paintbrushes, canvases, some reference books. But there were new elements as well. Music played constantly in the background: devotional songs that set a mood for the work at hand. Sometimes two or even three artists at a time worked to complete a painting, each contributing his or her best effort, either in background design, facial details, jewelry, architecture. The artists, in their discussions, constantly referred to Vedic scripture. Clearly they had studied the history of their subjects well, and they drew details for the work from the ancient texts.

I asked one young man where he had received his training. He had graduated from a well-known art school, he said, and after becoming a devotee he had gone to India. What was an artist’s training like in India? “Oh, very intense,” he said. “An artist in the devotional tradition never attempts a sculpture or painting of Krishna unless his teacher has sanctioned both the work and his readiness to execute it. The forms of Krishna are divine; when depicted by one who is not in the proper devotional mood, the result can be unintentionally offensive.”

I noticed a young woman prepare her brushes by washing them in a sink down the hall. There was a bathroom closer by, but, she explained, through the agency of these brushes Krishna would appear on canvas, and so she preferred not to wash them in the bathroom. Before applying the first strokes to her canvas, she folded her hands and offered Sanskrit prayers before a picture of her spiritual master.

The artists were trained technicians in their craft. In the sculpture workshop a heavyset man with a clean-shaven head applied filler to a bust of Old Age, a character in a diorama depicting birth, death, and rebirth. He looked at the bust, and, for my benefit, broke down the visual impression into colors, contrasts, perspectives, relationships, planes, and other aspects that had escaped my untrained eyes.

Yet beyond technical prowess, the artists were depicting Krishna in minute details. They pointed them out to me: flowers leaning toward Krishna’s feet, birds observing Him from the branches of trees, in the rainclouds hovering in the distance, intentionally abstaining from disturbing Krishna’s playing with His friends. The artists described as well their appreciation for the very tools of their trade. Krishna was in the earth and clay that made up their paints. He was in the water that washed the brushes. He was the light of the sun that illuminated their studio. Nothing in their work was separate from Him, and by His presence the work itself became transformed into an act of meditation and prayer.

I asked several of the artists what they felt was the most important part of their work. Though one or two spoke of abstract concepts such as detachment from the finished product, they agreed that the most important part of their work was a strong daily program of morning sadhana, the devotional and meditative practices that begin around 4:30 a.m. and end by 8:30 a.m. in every temple of the Krishna consciousness movement. Without that regularity of spiritual discipline, they all agreed, they could never put brush to canvas or chisel to stone.

Over the course of the last few years, my deepening appreciation for spiritual art has cast in a different light the culturally based ideas of art that I grew up with. Instead of a progressive development in the arts, the contents of our museums seem to evince man’s increasing estrangement from his spiritual roots. The further we divorce ourselves from the notion of a higher being and a life beyond matter, the more abstract and cerebral and sterile our artistry grows. And what usually passes as spiritual is in fact merely a negation of what we take to be material: form, personality, recognizable elements of creation. As a result, the spiritual reality, a world filled with variety, form and personality remains hidden from our view. That spiritual reality, says the Bhagavad-gita, is revealed proportionately as we step away from the egoistic notion that “I am the creator” and “I am the artist” and step closer to acceptance of his role as an intermediary, a conduit for God’s artistry.

Even an untrained devotee artist can become such a medium. This is true because the transcendental quality of a work of art is a result not of technical skill but of the artist’s purity of devotion, his desire to glorify God through his work. Properly guided, even an unskilled devotee artist can bring out the Supreme Spirit for all to see, as exemplified by the following anecdote told to me by one of the artists in Los Angeles.

Once, while traveling by plane, Srila Prabhupada chanted Hare Krishna on his beads while meditating on a drawing of Krishna pinned to the back of the seat in front of Him. This is a common practice among devotees who travel, but it was striking that Srila Prabhupada had chosen this particular drawing to meditate upon. It was done in crayon: the unpretentious, untutored work of a child. It had little aesthetically redeeming value. To Srila Prabhupada it was finer than a Rembrandt, more meaningful than a Degas, more intriguing than a Picasso, because it was Krishna drawn by the loving hand of His young devotee.

In that simple sketch was abundant subject matter for Srila Prabhupada’s artistic contemplation: devotion, sincerity, earnest labor, and a six-year-old’s humble offering of love to God.