People as products of history and the yogic remedy

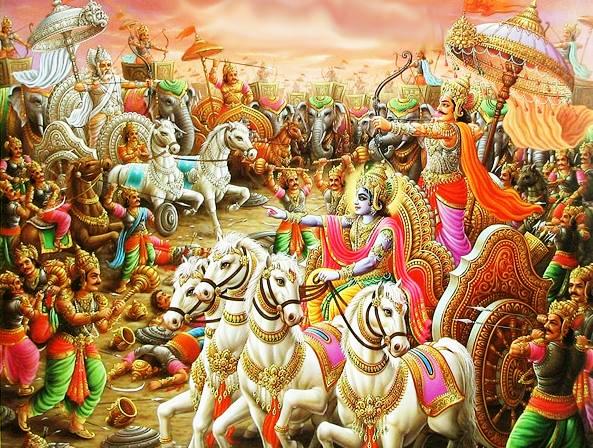

“One should engage oneself in the practice of yoga with undeviating determination and faith. One should abandon, without exception, all material desires born of false ego and thus control all the senses on all sides by the mind.” (Bhagavad Gita 6.24)

The term “kama” in this verse is fascinating, defined here as “material desires born of false ego”—in simple language, anything that does not bring one closer to our non-material self. When I was younger, I had a young person’s understanding of kama, namely sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll. With time, I began to see that art, education, even philanthropy and science, can be kama if undertaken without a spiritual purpose. Actions in these realms may be situated in sattva-guna, goodness, but sattva is not transcendent as “goodness,” too, is motivated by ego. Maybe a cleaner ego or less harmful, but still binding. “Good” people according to Gita also have to be reborn, in order to reap the rewards of their prior good deeds.

This moment historically is a fascinating time to track kama at work. How did we become a society so obsessively focused on the material and so consistently ignorant of the spiritual?

Max Weber was a 19th century German scholar who is credited with inventing the field of sociology, along with Emile Durkheim in France, Herbert Spencer in England, and W.E.B. Du Bois here in the States. Weber looked at the rise of capitalism and saw something interesting: that in the 17th and 18th centuries an industrious nature geared to the acquisition of wealth was condemned as irreligious. God preferred His children pious, not productive. “It is easier,” the Bible proposed, “for a camel to go thru the eye of needle than for a rich man to enter Heaven.”

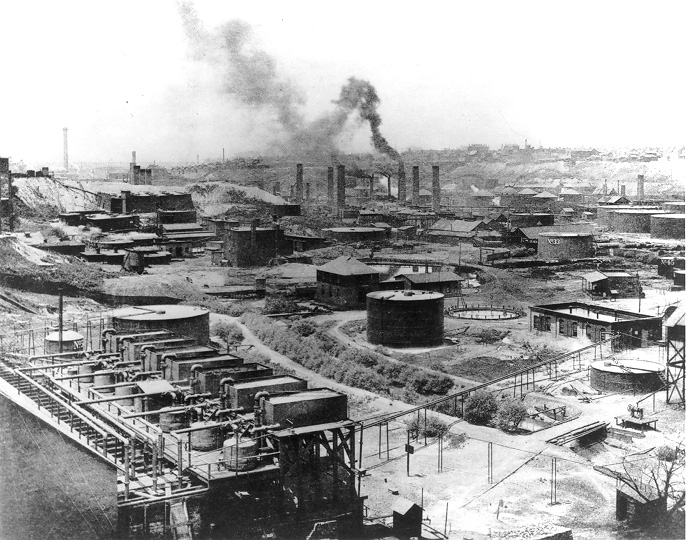

Then along came the industrial revolution, and Weber noted that capitalism overtook its religious predecessor by redefining the meaning of “pious.” Capitalism, Weber noted, was not just a set of financial transactions but an attitude that bordered on religious. The capitalist definition of God’s will for humanity was to pursue piety within productivity. After all, had recent discoveries not proven that God’s plan was for the pious to become wealthy?

Case in point: the American oil industry, which began around 1870 when John D. Rockefeller formed Standard Oil. Two years later, Rockefeller formed Standard Oil Trust: a monolithic umbrella entity that housed more than forty Rockefeller companies. The Trust quickly became the richest, biggest and most feared business in the world.

Here’s what you need to know. Rockefeller was guided by his religious beliefs, and for him oil had a divine purpose. The underground riches were there, he said, to help establish God’s Kingdom on earth. Oil was “the bountiful gift of the great Creator” and a “blessing . . . to mankind.”

Rockefeller was not alone in this assessment of oil as a gift from God for perpetuating His plan in the world. After World War I, oil barons were funding Christian institutions such as Baylor University. One of Baylor’s graduates, Sid Richardson, became a millionaire in the oil industry and a major supporter of Evangelist Billy Graham.

You may have heard the names of some of the other oil-wealthy families such as the Hunts and the LeTourneaus. How about Oral Roberts and Charles Fuller, among America’s first televangelists? They used their oil profits to fund ministries.

By the 1920s, the work-ethic was firmly entrenched in mainstream thinking. Work hard and God will reward you with riches and comfort. Well, here’s the upshot. Quickly people realized that if the goal was wealth, and if wealth was obtained by working hard, then why bother with God at all? If there is a God, He rewards our hard efforts. And if there isn’t a God, hard work gets rewarded anyway.

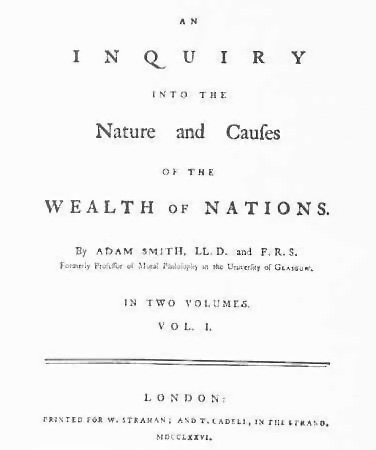

Weber concluded with this tragic prediction: “Today this [American free market consumer capitalist] system determines not only the life of those directly involved with business, but of every individual who is born into this mechanism—and may well continue to do so until the day when the last ton of fossil fuel has been consumed.” This is 100 years ago! Weber was tragically prescient in his prediction of consumerism’s impact on the environment. If you go back to the roots of economic theory—Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes—they all saw work and capitalism as a means for serving the interests of humanity, and they assumed that nature was this unlimited resource from which hard-working consumers could keep drawing down forever. We’ve been dealing with the consequences of that illusion ever since.

These then are some of the historic roots of the American obsession with hard work and consumption—what this verse of the Gita describes as “material desires born of false ego.” The tools of market economics—Facebook profiling and other aggregating of personal information—assure that it will be nearly impossible to extricate ourselves from that system—nearly, but not wholly impossible.

In this verse and elsewhere in the Gita, Sri Krishna reminds us that by cultivating inner vision, through yoga, meditation, and well-guided study, we can reawaken our true selves, the non-consuming selves we were meant to be. I like what Jimmy Fallon said recently: “I don’t want to be another white guy who just says ‘Let’s be the change.’ I want to know what the change is. What is it we’re meant to be?”

He didn’t answer that, but it’s the right question. The Gita’s answer, the yoga-culture answer, is: “Stop defining life by what you can measure. That’s the tip of the iceberg.” When we think we are this body, then sooner or later our bodies and life itself become commodities within the capitalist system (seen viscerally in factory farming and bio-engineering).

The material self is of course part of the reality—for instance, I’m a Jewish, white male, vegan, centrist democrat. That’s the external part: it’s variable. I’d vote Republican if the right candidate came along. What is the invariable part? What is the unchanging common ground of all life? Consciousness.

Let’s be clear about this: a philosophic appreciation that we are non-material consciousness does nothing to alleviate historic realities. But we should never think that the Gita speaks in theoretical abstractions. Remember, at the conclusion, Arjuna goes to war. The time can come when good arguments fail and we have to take to the streets. And if that time comes, then we should do that—but if our actions are going to achieve long-term change, they would benefit from a grounding in awareness of all beings as non-material consciousness.

Along with oversight in our efforts for social reform, let’s include a measure of insight. Permanent solutions to social issues demand an understanding of our true selves, the selves that exist with or without the elusive social justice we all crave.

For his acts of greed, Zeus’s mortal son Tantalus was made to stand in a pool of water beneath a fruit tree. Whenever Tantalus reached out, the branches rose away. Whenever he bent to drink, the water receded—cursed to being forever “tantalized.” This verse from the Gita reminds us that however drawn we may be to the “fruits” of an illusory world, nothing compares to the “higher taste” (param-dhristva) of a yogic life of devotion to God.

For his acts of greed, Zeus’s mortal son Tantalus was made to stand in a pool of water beneath a fruit tree. Whenever Tantalus reached out, the branches rose away. Whenever he bent to drink, the water receded—cursed to being forever “tantalized.” This verse from the Gita reminds us that however drawn we may be to the “fruits” of an illusory world, nothing compares to the “higher taste” (param-dhristva) of a yogic life of devotion to God.

My spiritual master, Srila Prabhupada (1896-1977), used the phrase “Krishna conscious” to describe the soul’s original state of love for God and all God’s creatures. This original nature is instinctively self-sacrificing or “without attachment.” In an interview with commentator Bill Moyers, mythologist Joseph Campbell remembered an event from the 1980s that underscored this compassionate impulse.

My spiritual master, Srila Prabhupada (1896-1977), used the phrase “Krishna conscious” to describe the soul’s original state of love for God and all God’s creatures. This original nature is instinctively self-sacrificing or “without attachment.” In an interview with commentator Bill Moyers, mythologist Joseph Campbell remembered an event from the 1980s that underscored this compassionate impulse.