More Than Words on a Page

Memories from travels with a realized soul

Teaching Bhagavad Gita and other Bhakti texts poses a challenge even for seasoned devotees. How do we convey in a relevant way Sanskrit teachings that date back thousands of years? Many devotees offer a simple answer: it’s all there in Srila Prabhupada’s commentaries or “purports”. As a pure devotee, his explanations contain profound spiritual insights. They are perfect and complete, so just read and follow. Okay, but some things are not directly explained in his books, such as what to do about climate change or how to correct social injustices.

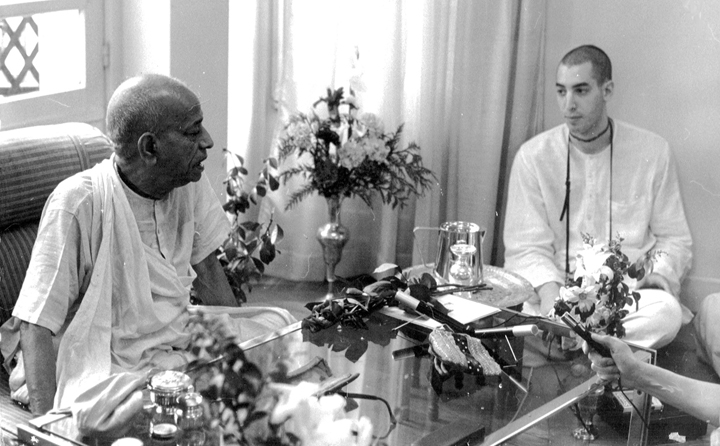

Sometimes, during the years when Srila Prabhpada was with us, it seemed the only way to understand a particular passage was to ask him personally. I remember one occasion in September 1973, when he visited Paris for the first time. It had been a long day for him. He had flown in from Moscow and arrived at Charles de Gaulle Airport only a couple of hours before a press conference in the offices of Air India Airlines. About twenty devotees attended his talk with reporters. The discussion lasted more than an hour, and by then we were anxious to bring him to our tiny house in the suburbs so he could rest. As someone who spoke French and knew the geography of the city, I had the honor of driving him to Fontenay aux Roses, the village where we had rented a house. It wasn’t much: the temple room was in the garage. But it was big enough for Srila Prabhupada and his assistant, Nanda Kumar, to have their own rooms.

Our car arrived ahead of the other devotees, who were returning by the Paris metro, and for the next hour I was alone with Srila Prabhupada while Nanda Kumar cooked his lunch downstairs. Prabhupada asked me to help him unpack, and when the unpacking was done I stayed in the room. A private audience was a rare privilege, and I was ready to take full advantage. He sat down on a cushion, closed his eyes and chanted quietly on his beads. I sat across from him on the carpeted floor and chanted along for a few minutes. Then, mustering my courage, I asked him several questions that had puzzled me ever since my initiation two years before.

“May I ask you, Srila Prabhupada, about the gopis’ love for Krishna?”

He opened his eyes and cocked his head to the side, as though saying, “That’s a pretty big topic for a pipsqueak like you.” I barreled ahead.

“In your books, you write that the gopis’ see Krishna as their lover, and that their conjugal affection for him is the highest expression of love for God. Is that how you want us to love Krishna? I mean we, your disciples. Should we love Krishna like the gopis do?”

He considered the question. Nothing in his expression or posture suggested that he was offended or unwilling to discuss a topic far above my paygrade. “That’s very nice, if you want to do that,” he said. “But you have to be completely free from all material desires. For now, you should read: Caitanya-caritamrita, Caitanya-bhagavata…”

Wait a minute, I told myself. He hasn’t translated the Caitanya-bhagavata. Why would he want me to read a book he hasn’t commented? For reasons that to this day escape me, I failed to ask. Instead, I said, “In your books, you describe so many ways to love Krishna: as a servant, a friend, a parent, but it seems our tradition emphasizes the love of the gopis.”

“Generally,” he said, “the followers of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu follow in the footsteps of the gopis.” Then he quoted a verse from Mahaprabhu: ashlishya va pada-ratam pinashtu mam / adarshanan marma-hatam karotu va / yatha tatha va vidadhatu lampato / mat-prana-nathas tu sa eva naparah.

“I know no one but Krishna as my Lord, and He shall remain so even if He handles me roughly by His embrace or makes me brokenhearted by not being present before me. He is completely free to do anything and everything, for He is always my worshipful Lord unconditionally.”

“Ultimately,” Prabhupada concluded, “it is a question of personal choice.”

Personal choice? I’d never heard that before. My understanding was that the soul has an eternal relationship with Krishna, and when the soul becomes fully Krishna conscious that relationship resumes. “So, if it is a question of personal choice, wouldn’t everybody want to be a gopi? Why do some devotees serve Krishna as a cow or as grass in the spiritual world? Isn’t that less than the love of the gopis?”

“Why less?” he said. “In the spiritual world, whether you are a cow or grass or whatever you may be—if you are a big glass or a little glass, when you are full, you are full.”

I don’t think I would have understood that point about personal choice, had he not taken the time to explain it to me. I was an avid reader of his books, yet here was a fundamental principle of Krishna consciousness that had eluded me.

“Sometimes, Srila Prabhupada, we don’t have you so nearby to explain things for us,” I said. “What should we do if we can’t find an obvious answer to a question directly from your books?”

“There are two things,” he said, “lokiki and vaidiki. Vaidiki means it is there directly in the texts. Lokiki means according to the situation, and you use your best intelligence. Both ways are valid.”

His reply cleared up a lot of my confusion. I recalled an explanation he had given on other occasions, that there are two kinds of “bhagavatas,” or forms of knowledge: the book bhagavata and the person bhagavata. Prabhupada once described his books as “law books that will guide humankind for the next 10,000 years”,1 but books will always need explanation according to lokiki or particular circumstances. I’ve spent the past ten years researching the role of law during the Nazi era, and if we have learned anything about that dark time it is that law books are easily distorted, misappropriated, and bent to serve selfish ends. “The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose,” Shakespeare wrote.2 In spiritual life, as in law, books contain more than words on a page: they contain truths that depend on analysis and explanation by those who serve those truths with integrity and impeccable character.

There was an amusing follow-up to the discussion with Srila Prabhupada. The net morning, I was asked to give class in the temple room, which was directly beneath Prabhupada’s quarters. After class, he had Nanda Kumar bring me to his room.

“Was that you giving class just now?” he asked.

“Yes, Srila Prabhupada,” I said, anxiously awaiting some words of appreciation.

“You quoted many Sanskrit verses,” he said, nodding his head back and forth and making me feel quite proud of my performance. Then he pulled the rug out from under my bloated opinion of myself.

“Very good!” he said, raising his eyebrows and nodding in mock admiration. “Do that. They will think you are a bigggg scholarrrrrr…” His eyes grew big and he laughed as I turned bright red with embarrassment.

It takes more than a good memory for verses to achieve true scholarship.

2 Spoken by Antonio in “The Merchant of Venice”.